Hello and Welcome to this week’s Dropout Classicist Newsletter! In this article, I cover Aeneas, the son of Aphrodite, warrior-prince, and city founder. Spoiler warning for Virgil’s Aeneid, though you have had over 2000 years to read it! And if you enjoyed, but aren’t yet subscribed, feel free to do so. It helps support my work!

The heroes of the Trojan war are almost all household names nowadays. Achilles, Odysseus, Agamemnon, Ajax, and Menelaus pop up in new portrayals left, right and centre, whether it be the likes of Song of Achilles, or Stephen Fry’s Greek Myth series. The Trojans get some share of the spotlight too, but most of that is hogged by Hector and Paris. The Trojan side is filled with equally interesting heroes, and perhaps none more-so than Aeneas.

To discuss Aeneas, we must first cover the odd circumstances of his birth. According to the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, Zeus, was annoyed that Aphrodite held such power over him and the other gods, causing them to fall in love with whomever she wished. Zeus himself was constantly falling in love with mortals (well, lust would be more accurate than love), and instead of deciding to examine why he kept cheating on his wife, he thought it more fitting to blame Aphrodite. Thus, he decided to make her fall in love with a mortal. Descending to Mount Ida, her eyes fell on a young shepherd, Ankhises, and she was head over heels in a heartbeat.

Aphrodite approaches Ankhises in disguise, trying to sleep with him. Despite the fact he sees through the disguise almost instantly, he goes along with it. The next morning, she reveals herself to him as a Goddess, and he likely was not all that surprised. She then takes off in a fit of anger, promising the son fathered by Ankhises will be returned to him in a few years, and that if he dares to mention to anyone that he slept with the goddess of Love herself, he would meet a horrible fate. Despite how angry she seems in the moment, later writers believe she still doted on Ankhises, albeit from afar. Ovid claims she even considered gifting him immortality when given the chance. However, she did fulfil the promise of the horrible fate. Unable to keep the secret, he brags. Thankfully, he is not killed, but is still struck by a lightning bolt leaving him unable to walk properly.

Aphrodite’s son by Ankhises was returned to him as a toddler, as per her wishes. Thankfully for Ankhises, who was now both disabled and a single father, his family offered to help take care of his demigod son. Who was this family? Well, Ankhises just so happened to be a cousin of King Priam of Troy, the very same Priam who fathered Hector and Paris. This does beg the question as to why Ankhises chose to be a shepherd, but clearly this must be a pastime of some sort for Trojan princes, as varying sources tell us that both Paris and Aeneas were shepherds on that very same mountain at different points. I suppose there was little else to do in those days, after all reading and writing had barely been invented yet.

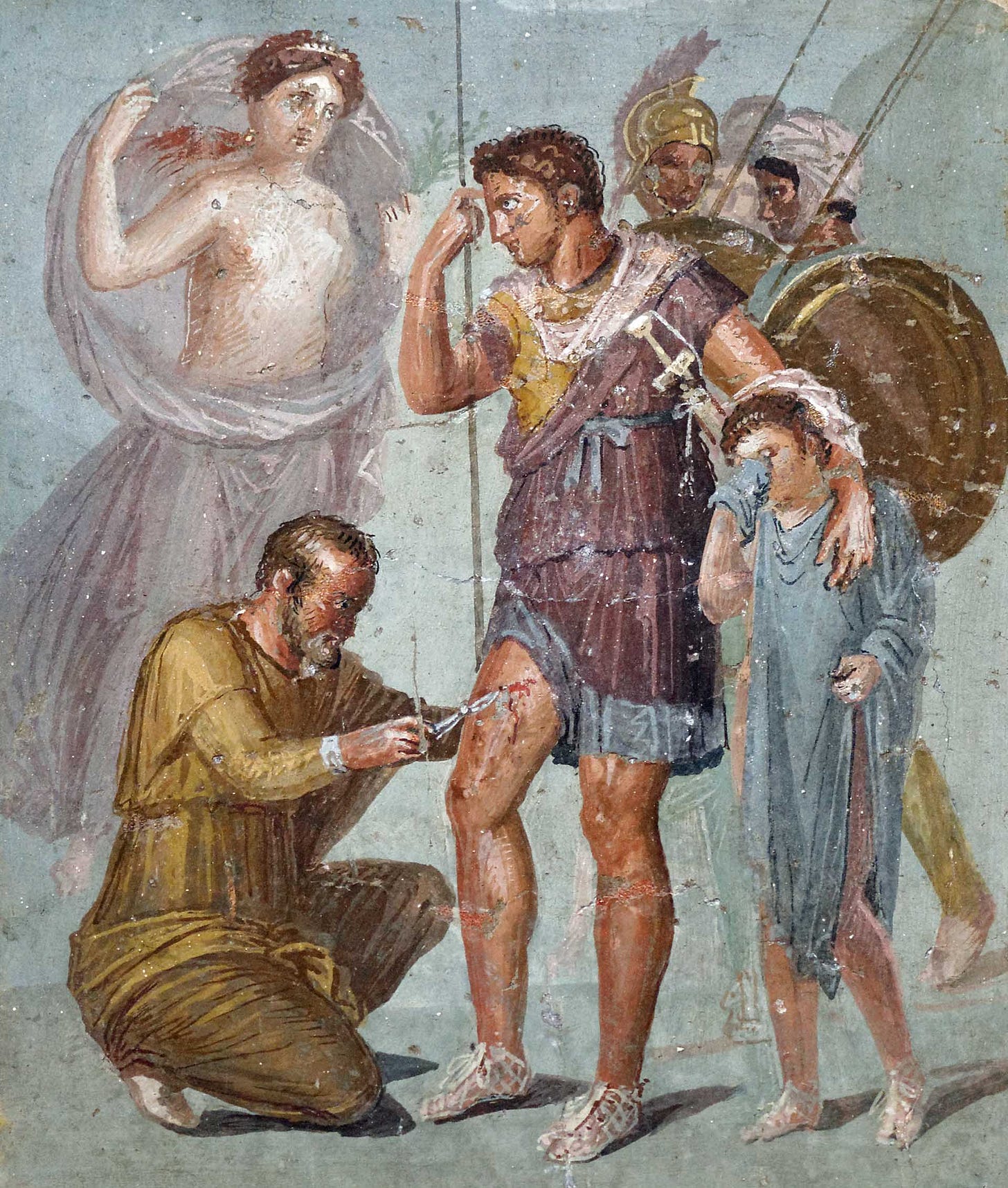

Thus, Aeneas grew up close to the Trojan royal family. We know little more about his time before the war, but he must have had a typical princely upbringing among his many royal cousins. Also, we know he married, his wife’s name being Creusa, and had a son, Ascanius. It is also heavily implied by a certain Roman writer that Ankhises lived with him in the city of Troy, and that he took care of him. When the Trojan war began, Aeneas obviously joined the Trojan side. As a member of the royal family, he took a generalship role, though evidently an insignificant one. Our sole surviving primary source for the Trojan war, the Iliad, puts him in a fight against Diomedes. In this very same book, Diomedes defeats both Ares and Aphrodite, so it is without question that Aeneas is comparatively a minuscule threat. Diomedes defeats him, but he is whisked away by his mother and Apollo to a safe spot before Diomedes can take his life.

Besides occasional skirmishes, Aeneas is not all that relevant to the Trojan War. His moment of glory comes after. He is one of the few who fought and survived, after the Greeks defeat many of his comrades (some, like Sarpedon, even being a son of Zeus). We could imply from his lack of an explicit death scene that some other myth existed contemporary to the Trojan cycle that attested for his fate, but no such story exists. Rather, no such story exists until the Romans got their hands on him.

Though he had found his way into the Roman foundation story before, we can attribute the fame Aeneas holds today to one author alone: Virgil. Writing in the late 1st century BCE, Virgil takes this relatively minor Trojan prince and reforges him in a compelling epic poem, casting him into a complex, twisting and emotional narrative of fate, gods and tragedy. Virgil’s Aeneid, which I shall be spoiling from this point on, has often fallen under the radar in pop-culture, though for fans of the Iliad and Odyssey I believe it is a fantastic read.

Virgil begins Aeneas’ story in medias res, but I will be following it chronologically and in summary. Beginning where we left off, and skipping the interlude wherein the Trojans bring the horse into the city, Aeneas is visited in a dream by the corpse of Hector, warning him to flee Troy, and telling him his fate is to found a city elsewhere. Aeneas, waking with a shock, steps outside to find his entire city lit up in flames, Greek soldiers running rampant. It is a scene of horror, as Aeneas rushes into battle to help where he can. He witnesses the brutal murder of Priam, supplicating himself to Neoptolemus, and the innumerable other crimes against the Trojan people. He has no other choice but to flee, carrying his injured father and young son. His devotion to both is unquestionably admirable. His wife however is lost in the crowd and chaos, but her ghost tells Aeneas to go on without her.

Setting off, amidst a fleet of the few surviving Trojans, Aeneas becomes obsessed with founding this new city. He tries to found one in Crete, but to no avail. He tries near Thrace, but no luck either. He meets up with Andromache, Hector’s widow, and Helenus, his fellow Troy survivors, who have both been freed from slavery by the murder of Neoptolemus. These two have founded New-Troy, but Aeneas decides not to stay. He must build his own walls. When reading this part of the Aeneid, especially in contrast to the prior massacre we have just read, Aeneas seems almost stroppy and jealous. Nonetheless, he continues wandering until he ends up shipwrecked on the coast of Carthage.

Dido, recently widowed Queen of a newly founded Carthage, greats him warmly. His travels have been tough, though he is yet to lose many people besides his father. He recounts his tale to her over dinner, and she falls for him (though this is mostly his mother’s doing). The two fall in love, and Aeneas starts to believe he can finally stop running. He finally fulfils his wishes of building a city wall, and he is placing bricks to build up Carthage when a visitor finds him.

Mercury (Hermes, but the Roman names must be used from this point on) has arrived with a message from Jupiter (Zeus). Aeneas is not fated to be king of Carthage, and he must leave. He has no idea how to tell Dido, but cannot disobey the gods. In the end, his leaving results in her tragic death, as she cannot bear to be left by him. Aeneas, though saddened, is shockingly unfazed by the death of his second love, though come to think of it he was quite unfazed by the death of the first one. Nonetheless, he sails forth to Italy. After funeral games for his father, and a quick stop to pick up a straggler from Odysseus’ crew, Aeneas reaches Cumae, close to Naples.

Aeneas’ adventures in Italy begin with a trip to the underworld, followed by diplomacy, a hunting accident and then all out war. To keep it simple, a local prince named Turnus is driven mad by Juno (Hera) when Aeneas arrives, as his presence threatens his potential marriage to the princess Lavinia. Lavinia, tragically, has no say in the matter at all. In fact, I do not believe she has a single word of dialogue in the poem. Nonetheless, the conflict is bloody but short. We are given yet more horrifying descriptions of war, to which I can do no justice, and Turnus murders the youth Pallas, for whom Aeneas is responsible. The poem ends on Turnus’ death, where he begs for salvation before Aeneas as his madness fades. Recalling Pallas though, Aeneas shows no mercy. We are left on this climax, and all the implications it leaves.

So, why did I make you read over 1000 words of Aeneas’ story? Well, his character is arguably one of the most interesting of any hero. Unlike most sources from the ancient world, which we assume to be based on pre-existing stories, Virgil is mostly working from the remnants of Homer’s work to spin a whole new founding narrative. We can see this most in Aeneas’ wanderings, which take place after the dust of the Trojan War has already settled. The sun is rising on a new world. Most of the old heroes are dead or retired, and Aeneas is the last of a dying breed.

This is clearly Virgil’s intent for his poem. Aeneas’ depiction, though often flawed, is undoubtedly in stark contrast to the other heroes of myth. He is equally as flawed, but is a lot less self-centred. If anything, he is more of an idealised politician than a hero. However, he is too often a puppet for the gods and fate, a predicament that often feels him feeling a little flat.

Aeneas’ characterisation, and the Aeneid as a whole, are a masterwork when we consider what Virgil is doing. Without going into too much detail on this aspect, the entire poem is clearly a propaganda piece for the Emperor Augustus, yet it is also so much more. Virgil takes the embers of myth, just before they become history, and reignites them for one last inferno. He utilises the scraps left over, building a founding narrative for the city that conquered the world. The Romans often saw themselves as a cultural follow-up to the Greeks, hence why so much of Greek culture is carried across into Roman lives, and Virgil’s poem almost acts as a rewriting of that transition. He ties up the last few of Homer’s loose ends in his process of writing Rome into the narrative of the gods.

Aeneas began life as just another name. If not for Virgil, he likely would have just been a footnote, a product of the gods’ mischief and just another Trojan captain to be defeated. Virgil takes the generic hero we see in just a few pages of Homer, and gives him something all of his own. He serves so many purposes, not only in a compelling narrative. He acts as both a critique and glorification of Augustus, who at the time was the recently crowned ruler of most of the known world (though I admit I have touched on very little of the propagandistic and political aspects of the poem). But to me, what is most interesting about Aeneas is how he became this. Many mythological figures take their roots in reality, like Midas, as I covered here, but Aeneas is a truly rare example of the exact opposite. He existed beforehand, though in a generic fashion, and was spun into an entirely new narrative. He is a projection of Roman anxiety and pride, and thus serves as one of the earliest mythical retellings. It is remarkable how Virgil builds us a character on so little, working within the frameworks of the pre-existing mythology and constructing a new narrative without stepping on the works of any of the storytellers who came before him. Thus, I think we can forgive Aeneas some of his flaws. After all, for hundreds of years he had no story to tell at all.

Sources:

The Aeneid, Virgil tr. David Raeburn

The Aeneid, Virgil tr. Robert Fagles

Metamorphoses, Ovid tr. David West

The Homeric Hymns, tr. Michael Crudden

Aeneas and the Roman Hero, R. D. Williams

Rubicon, Tom Holland (for political research on the rise of Augustus, which I did not end up using)

Age of Augustus, ed. A Cooley (see note on source above)

I always thought Aphrodite couldn’t fall in love, but after reading this, I decided to research it more. I really enjoyed this and found myself completely engrossed in the story 🫶🏻