Hello and Welcome to the Dropout Classicist Newsletter! Today we will be covering the surprising beauty of Pompeiian graffiti, plus a historical mystery! If you enjoyed this, and want to read more on Ancient History and Mythology, please consider subscribing!

Every now and then, a post on Pompeiian graffiti gains traction on the internet. Normally, it ends up on my feed. This is not only because the algorithms have pinpointed my taste better than I probably ever could, but also because I, like many others, find some of this graffiti to be amusing, and incredibly touching.

You may know the sorts posts I am talking about, though like many I have tried to discuss them with, I don’t doubt they are more niche than I assume. To summarise, they typically include a translated, curated list of some of the more funny and touching highlights.

“Whoever loves, let him flourish. Let him die who doesn’t know love. Let him die twice over whoever forbids love.” CIL 4.4091

The writings scrawled across the walls of Pompeii vary in purpose and authorship, as you would expect. Some are political slogans, some lovesick poetry as above, some advertisements, some crude messages or insults, and some word games, and some references to ancient literature. They are almost all unique, in varying hands, made at varying times and dotted in some of the most unexpected places. They are in no way dissimilar to what you may find in a modern town.

This is their beauty, though it is often an odd sort. Of course, some of the graffiti is brilliant in isolation, like the poetry and jokes. But they are all combined in a brilliant, joined, contextual beauty - that of humanity. It is easy to look at the past and see the barbarity, the big names or the various differences. It is pieces like these that remind us that, deep down at least, we have not changed much. It is easy to look back to the past and see the people who lived it to be something other, but to do so is wrong. The past is a mirror, and Pompeiian graffiti should remind us of that.

“On April 19th, I made bread.”

When looking at some of the examples, I find myself at an inexplicable loss for words. The one I have picked out above is one that hit me the hardest. It is carved in the gladiator barracks and, though hard to tell the sentiment, the simplicity of the statement feels so resonant. It is impossible to know the person who wrote it, but haven’t we all felt the same sense of achievement and pride when we have baked something, crafting it with our own hands? The only difference is that now, instead of carving our joy on the wall, we would post it on social media, or rejoice in the victory of creation by texting a friend. I baked bread the other day too, my friend from the past.

The various drawings and carvings left on the walls can tell us so much more about the people living in Pompeii than we expect, and by doing so they only break our heart further knowing the way the city met its end. None do this more than those we presume were left by children. Crude stick figure drawings of gladiators, doodles and word games don’t look too dissimilar to the sort of stuff I find in the back of my own old schoolbooks. One that resonated with me is the one above, a drawing of a maze with the caption Labyrinthus. Hic habitat Minotaurus. In English: ‘The Labyrinth. Here lives the Minotaur’. Not only does this prove a familiarity with Greek mythology, but also that it was present in the imagination.

“We two dear men, friends forever, were here. If you want to know their names they were Gaius and Aulus.” CIL 04 08162

From all the Pompeii graffiti, anyone who has used Tumblr is probably most familiar with the ‘Gaius and Aulus’ inscription. This is the one that inspired me to write, after it almost brought me to tears upon reading again. No doubt I am not alone, as these two lines alone have inspired memes, posts and even fan-fiction (I have not read it, and am afraid to do so). People have theorised much about the authors of this inscription, to the point that it has feasibly worked its way into databases of LGBTQ sources from Ancient Rome. I will not comment any further on this, as I can find no scholarship on the matter, but it is a heartwarming if overly optimistic sentiment.

The resonation of these inscriptions, especially that of Gaius and Aulus, is so innately human. All of these people, though long dead, have left a mark on the world. They all are remembered, in some manner, which is a rarity from antiquity for the average citizens. But it is also one of our innate aspirations, or so I believe. After all, we can see this behaviour everywhere. A viking carved his name on the Hagia Sophia, claiming boldly to the world that ‘Halfdan wrote these runes’. Lovers scratch their initials in walls the world over. As I researched this article, a man had just gotten in trouble for carving his own name on a wall in Pompeii, joining the masses of citizens who did so many years ago (please do not do follow his example, it is morally wrong and illegal). Is it not this motivation to be remembered, to live on long past our time, that drives so many artists, writers, scientists and innovators? So, how different were these Pompeiians to us after all?

If You Want To Know Their Names

When I planned this article in my head, it was supposed to end there. This was never supposed to be more than an essay about the eternal condition of humanity, our struggle with the march of time and our brief glimmer of existence. However, my research took a twist that I never could have seen coming, and one that I doubt many people know.

When I was searching through the various databases of Pompeiian graffiti and wall carvings, I found an image of the Gaius and Aulus inscription. My latin abilities, and my skills to read latin epigraphy, are limited, but even so I couldn’t help noticing something odd.

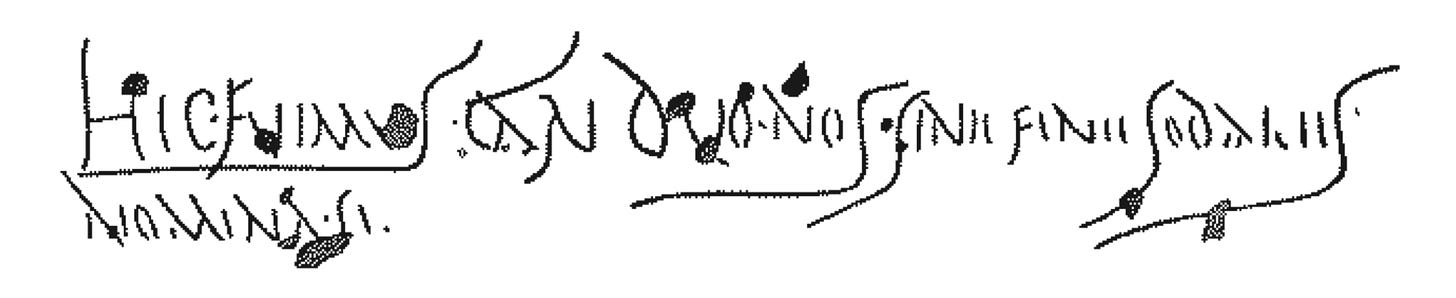

The latin should read hic fuimus cari duo nos sine fine sodales. / nomina si quaeris, Caius et Aulus erant. Gaius would have been spelt Caius, due to the lack of a G in the alphabet at the time. See if you can spot the names of Gaius and Aulus in the image above. The C and A should be easy to spot, surely? Most of the rest of the words are legible, but the text seems to cut off at ‘and their names were…’. Fading and damage to inscriptions over time is not something unusual, especially at a site like Pompeii. With so many tourists and so much exposed to the air, things will inevitably crumble. So, I decided to see if I could find any older illustrations of the inscription. This is where things took a turn.

I decided to do more digging, rummaging through obscure databases and reading ancient articles. No matter where I looked, this one image was the only one that kept cropping up. Eventually, I found an article discussing the excavations from Pompeii in 1912. There was a small mention of the inscription, and nothing published before seemed to ever mention it. This was it. However the archaeologists described the inscription was how it must have been when it was unearthed that year.

“Tantalising in its mutation”. The words stung. I was shocked, though there was still some hope. The archaeologists may not have found the text in a complete state, but they are clever. There are ways to piece together incomplete inscriptions, whether it be by cross-referencing them with others, or examining the walls to see if there are even the faintest traces. Or so I hoped that was the case. Disheartened, but still fuelled by the last dregs of my optimism, I kept looking.

I found nothing besides evidence to the contrary. Looking back over some other articles referencing the inscription, I saw a sign that my hunt was all for nothing. Lacunas, better known as gaps in texts, are typically marked by either ( ) or [ ], with writing in the brackets replacing the lost text. Sometimes writing in the brackets is something we know for certain, but often it is just a guess. The articles and papers referencing the text read like this: nomina si [quaeris, Caius et Aulus erant]. In translation: ‘We two dear men, friends forever, were here. (If you want to know) their names (were Gaius and Aulus)’.

So why are the names Gaius and Aulus in these texts? Well the lines follow a pattern of verse known as elegiac couplets. These little poems, only two lines, were very common in the Roman Empire. Their main use was for sentimental purposes, typically love poems, but the metre can be altered to make them poems about grief by cutting the last line short. This is symbolic, like the ending of a life before its time. You start the poem expecting a joyous ending, and your expectations are cut short when the poem is.

Gaius and Aulus complete this metre, that is why those names were chosen. Their addition gives the poem its happy ending, but we can never know for certain if those are the names that belong there. In a cruel twist of fate, the damage of time has removed their names, cutting short their happy ending. The inscription cannot be dated. It isn’t unreasonable to theorise that the eruption of Vesuvius cut it short, like the poem itself.

To those reading this, feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments. I am here. You are here. Let us rejoice in that.

Sources and Further Reading:

Mary Beard, Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town (Profile, London, 2008)

A. E. Cooley and M. G. L. Cooley, Pompeii, a Sourcebook (Routledge, London, 2004)

George H. Chase, “Archaeology in 1912. Part II.” The Classical Journal 9, no. 3 (1913): 102–10

Jerry Toner, “The Writing’s on the Wall: Reading Roman Graffiti” Antigone Journal (2009)

Pompeii in Pictures, J. and B. Dunn

That was very interesting. The bread inscription struck me, I love baking!

I’ll never tire of hearing about Pompeiian graffiti. Fascinating, wonderful stuff.