Hello and Welcome to the Dropout Classicist Newsletter! Today, I wanted to introduce Heinrich Schliemann to those unfamiliar with him, and give a brief intro to the discovery of Troy. Also, I would like to provide a short personal update at the end of this article, for those interested. Enjoy!

As children, we often dream of finding ancient gold, hidden treasures and relics of people long past. Archaeology is not a field where this happens as often as you would expect, though we love to imagine a roguish, grizzled, Indiana Jones style of ‘excavation’. Meticulous care and patience are required when studying the past — anything destroyed cannot be replaced. Everything on a sight can be valuable, even the soil itself. Archaeology is almost study of context as much as it is a study of objects, as an object without a context is ultimately meaningless. However, it has not always been this way. Not so long ago, when the past was much more obscure, the world of excavation was quite different.

Our story begins with Homer, as most things do if you extrapolate far enough. In his poems, he describes a totally different world, yet one we can mostly map onto modern geography. His Mycenae, Ithaca and Pylos align with ours, and even his mythical locations have a decently established geography (such as the land of the Cyclopes, often imagined to by Sicily). However, up until the mid 1800s, there was a notable exception: nobody knew where to find Troy. This is odd, with it being such a central location to the Greek cultural identity. What’s more, Homer describes it vividly, as though he had been. Around this time, the Victorians were starting to take greater archaeological interest in Greece, though looting would be a more accurate term in many cases. The lifting of the marbles from the Acropolis was fresh in the minds of the upper classes, and, though Greece had passed laws in the wake of it, everyone wanted to be the first to uncover something dramatic and new. A race began, for the wealthy to go down in history like the Greek heroes they idolised, by discovering something exciting.

A fresh approach must be taken, and ancient texts began to be scoured through for any hint of something worth uncovering. Homer was re-examined, and the debate of Troy’s location began. Homer describes Troy as being on the Hellespont, in modern Turkey, by the Scamander river and near two springs. Of course, it must be within viewing distance of the shore, where the Greeks camped. Two key sites cropped up, the desolate Hissarlik and a mound further inland. Hissarlik was known to be the site of the Hellenistic town of Ilion, which was another name for Troy, but the existence of Roman ruins seemed to make it less favourable. The other site was close to two streams, one hot and one cold, which Homer describes. Most Classicists began to favour the latter, but it was not a task for most Classicists, who at that time spent their days cloistered up with their books. No, it was a task for someone unexpected, who dramatically altered our understanding of Mediterranean history.

Heinrich Schliemann was a German businessman. He was fluent in 22 languages by the time he died, and had made his fortune in the American gold rush. He had little training in the Classics or Archaeology, rushing his doctorate. He was also a massive egotist, insecure, and incredibly brash. He kept many diaries, constantly switching between German, Greek, Arabic, English or whatever language he felt like at the time. It is in these diaries he tells us that as a boy he dreamed of nothing but finding Troy. This deeply flawed man, by pulling strings and splashing about his wealth, was about to shake up our understanding of the past. Retiring at 36, he set off for the Mediterranean. There, he performed a few illegal test digs in Ithaca, before setting off to visit the Hissarlik site. He returned desperate to begin excavations, confident that he was on the edge of discovering Homer’s mythical city. After a long fight with the Turkish government, he got his permit to dig.

Our primary sources around Schliemann are his diaries, and besides that we know little else about his excavations, besides the results he chose to share. We know he did not own the land. We know the work force was mostly comprised of locals that he paid relatively poorly. We know he had a supervisor from the Turkish government, who was present to permit any funny business and who Schliemann constantly tried to deceive. And finally, we know his brazen and brash personality was an exact twin to his frankly abysmal archaeological methodology. He was desperate to find treasure, specifically from Homer’s time, and cared little for anything from the varied layers he had to plough through. It is often claimed he was reckless enough to use dynamite on the site, though a source for this is lacking. However, it is clear that his archaeological conduct was abysmal, even by the lax standards of the time. His assumption that the Troy he sought was on the lowest strata of earth meant he tore through everything else above, casting it aside. He cared little for pottery or other ‘less valuable’ artefacts, and often contradicted himself on where things where found in his dubious site notes. His quest for gold and glory left the earth damaged, ruining many of the layers of history and casting a trail of destruction.

It is easy to look back on past methods in distain, but even some of his contemporaries viewed his methodology as poor. He is described as ‘digging his trenches as one digs potato fields’. Given that his methodology was met with contempt by Victorians, who often were careless when it came to getting results, shows quite how much was lost. The Smithsonian Magazine claims that Turkish archaeologists are still reeling from the losses to this day. What’s more, one of the layers he tore through is the one that was later hypothesised to be the Homer’s Troy. But none of that mattered to Schliemann, and it mattered little to the masses of the time. They cared most about the gold. The mania surrounding his discoveries was at a fantastic level, as not only had he proven that a mythical city existed, but he had also hit on something much bigger. The Troy uncovered was from the Bronze Age, before any known Greek history at that point. He kickstarted a rethink about civilisation as a whole, especially when, riding the wave of success, he went on to uncover Mycenae. From there, we get the name of the civilisation: Mycenaean.

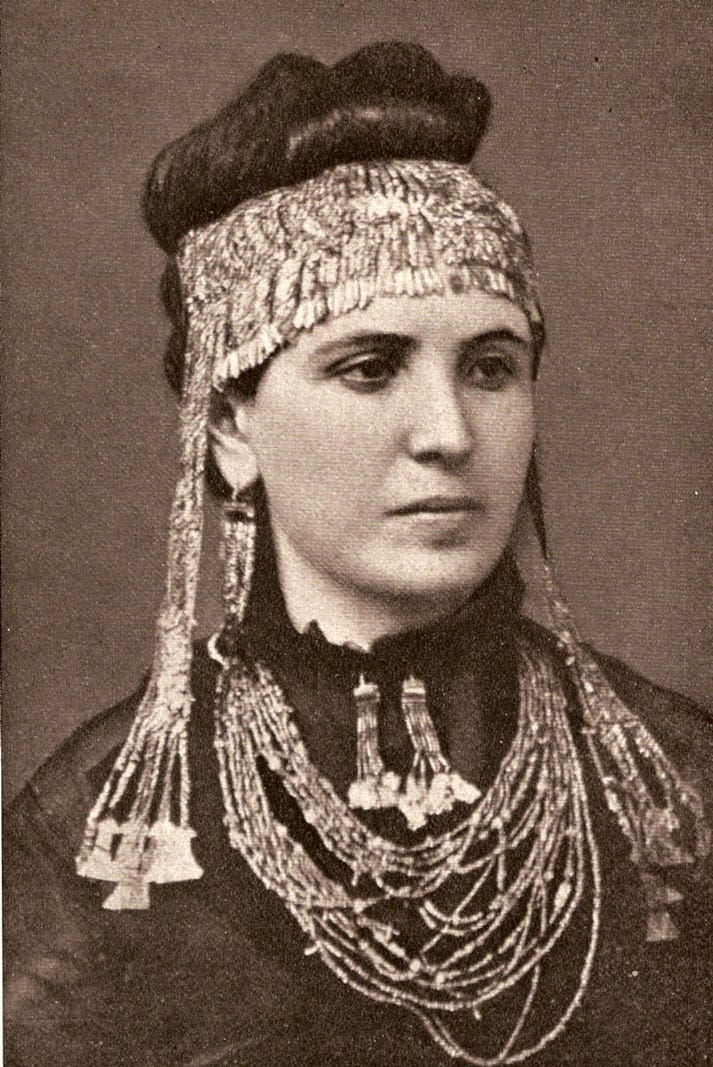

Schliemann did eventually find gold. In fact, he found quite a lot. Little of that gold went to Turkey, and most wound up in his mansion in Athens. Eventually, the Turkish government sued him for it and he paid them off, though this money was likely of little consequence to him. On his death, the gold went to Berlin. During the second world war, it was lost. It remained lost for about 50 years, before the Pushkin Museum admitted to having it in 1994, though many believed it would never be unearthed again. Nonetheless, the small parts that have been seen since are sometimes refuted, more-so due to Schliemann’s inability to provide providence than due to their disappearance.

Classics is not just a study of the Greeks and Romans. The field is so old that figures like Schliemann crop up all the time — disillusioned egotists with big dreams who impacted history in ways we could never predict. Schliemann is also a difficult man to deal with. For a while, thanks to his discoveries, he was credited as the founding father of Bronze Age studies. Much of his own writing contributed to that, as he focuses more on building a narrative than academic integrity. A similar methodology is seen in the names of his finds, which he dubbed the likes of ‘The Mask of Agamemnon’ or ‘The gold of Priam’ based on little more than his imagination. In spite of his horrendous technique, ego fuelled writing and poor morals, it must be admitted that our understanding of history would be quite different without his excavations. If not for him, a whole myriad of bronze age scholars would not have devoted their time to the field. Also, his usage of Homer as an archaeological source led to a re-evaluation of Homer’s work, who Homer was and the place that oral poetry held in an ancient society. Prior, the poems had been little more than poems, but now we know them to be almost miracles: they were stitched together, improvised art pieces containing a little historical inspiration, performed by an illiterate bard who could memorise thousands upon thousands of lines of poetry. So, we should not idolise men like Schliemann, as scholars often did in his time, but equally we should not despise them. His valuable contributions were made at great cost, and he will likely remain a subject of debate as long as there is history to study. But what can we learn from him? That we should take more care over things and learn from professionals, but also that sometimes revolutionary ideas must come from outside the box, and that we should keep an open mind. Anyone could have found Troy. And after the dust has settled, Schliemann’s name has gone down in history.

A Brief Personal Update

Hello! Thanks for reading! Some of you may have noticed that my newsletters have recently dropped to alternating weeks. I promise this is temporary. I have recently been a little ill, and have just not had the drive to throw myself into research projects, and may also explain any noticeable lack of writing quality in this post or ones prior. However, I intend to get back to weekly posting ASAP! I hope you are all well!

Sources

The Lost Treasures of Troy, C. Moorehead

The Bull of Minos, L. Cottrell

Ilium, H. Schliemann

Schliemann's Troy—One Hundred Tears After, M. I. Finley

The Many Myths of the Man Who ‘Discovered’—and Nearly Destroyed—Troy, M. Solly

I love this! really, is a necessary talk. Thank you for this! Also, hope you feel better soon :)