Hello and Welcome to the Dropout Classicist! This week, I beckon you into the cave of the oracle, to explore the mysteries of one of the most famous religious sites in the Ancient World. If you enjoyed this, and aren’t yet subscribed, feel free to do so! It supports the newsletter and you shall receive a new article weekly, direct to your email!

The oracle at Delphi was a crucial figure in the Greek world. Though featuring prominently in myth, her prophecies altered the course of greek history. State officials were sent to consult her often, and none more-so than the Spartans, for whom almost every decision had to be sanctified. The institution at Delphi told the future to many, from the average citizen to visiting nobles. But how exactly did her prophecies work?

You likely know the general gist of a visitation to the oracle. In a dark, strongly perfumed room, a maddened lady tells a cryptic rhyme. You, the visitor, probably do not know how to apply the advice she gives you. You then depart, get on with your life, and after time has passed you look back and see that what she told you was an encoded forewarning of events to come. Well, this is the trope at least. We see this everywhere, but especially in the writings of the Greeks and Romans themselves. Whether this be Oedipus, pre-warned that he would marry his mother and kill his father or Aeneas told he would eat his tables by the harpies, an oracle’s prophecies always rely on (sometimes questionable) hindsight.

Arguably, the most famous story of the Delphic oracle, the Pythia, is that of Croesus and the Persians, as told by Herodotus. I shall tell it in brief. Paranoid Croesus visits the oracle. It is the 6th Century, and the Persian empire is looming, stretching itself out towards the Greek world. Croesus wishes to inquire as to if he should submit his kingdom to them without a fight. His kingdom of Lydia, which is western Turkey nowadays, is right on their doorstep and looks to be their next target. The Pythia tells Croesus that if he attacks the Persians, a great kingdom shall fall. Croesus had prior tested the Delphic Oracle with a bunch of questions and deemed her responses to be truthful. Thus, he assumes that the prophecy indicates that Persia shall fall to him. Such hubris is the very factor that fulfils the oracle’s prediction, as the great kingdom to fall happens to be Croesus’ own. He realises this too late, as the Persians destroy Lydia.

Herodotus is not exactly a reliable source, and loves to include stories of dreams and prophecies in his narrative. For the ‘winners’ of his history, they are prophecies interpreted correctly, and vice versa for those who lose. There are many things to criticise about Herodotus (as covered here), but the most crucial to his recording of prophecies is his blatant attempt to moralise history, to turn the hubris or piety of others into a lesson for his readers. We shall take this into account later.

The Delphic Oracle, or rather the temple complex at Delphi where she resided, is well attested as being an ancient and well-revered institution. References to site, or at least an early version, are attested in the Iliad and an origin myth is recorded in the Homeric hymn to Apollo. In this, Apollo slays the mythical snake Python, guardian of Gaia’s oracle at Delphi, thus he takes over as the bestower of prophecies for the site. However, some modern scholars theorise that this myth had more humble origins, suggesting the snake had simply once been a local guardian of a spring, and that the myth was embellished in the 8th Century to match the growing power that Delphi held. Unlike similar oracles, like Zeus’ at Dodona, Delphi was incredibly well situated to receive visitors. Being quite central, and close to major powers like Sparta and Corinth, its fame and influence began to spread across Greece, then the Mediterranean. Wealthier visitors from afar, like the semi-mythical Midas (read this post for more on him), brought influence and treasures.

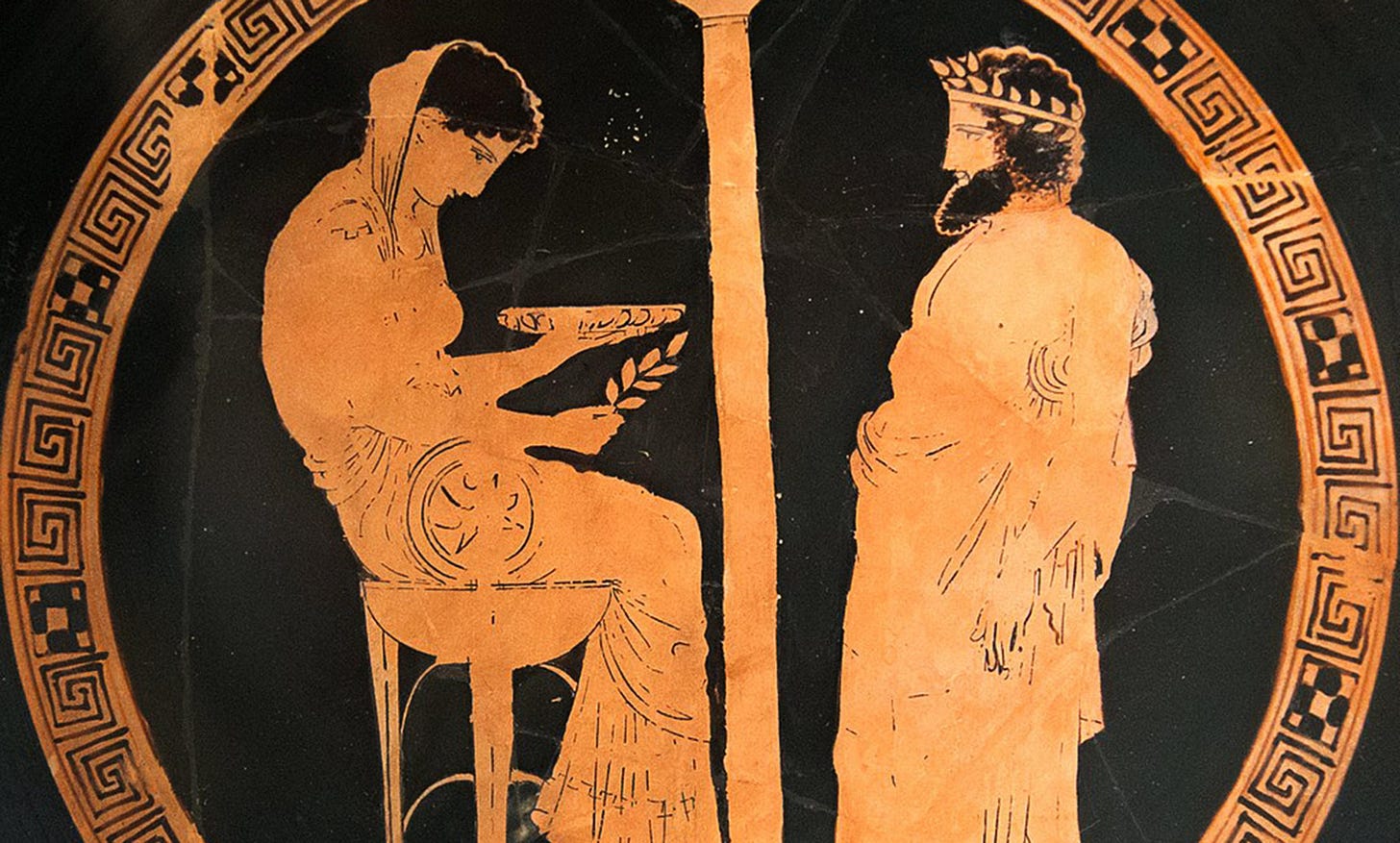

What would it have been like to visit the oracle and to ask her your questions? As far as we can tell, it was a heavily ritualised process. Your day likely began in a queue, as no doubt there were visitors to Delphi from all over. Then, when you got into the sanctuary, you were expected to be purified and make sacrifices to the gods. Asking the oracle a question was free, but the sacrificial materials were expensive (and conveniently available for purchase then and there). After this, you were allowed entry. You were led into a dark room with a priest of Apollo to act as your liaison. Likely, the room contained some form of theatrics: perfumes or a curtain to hide the oracle. You then addressed your question to the priest. No visitor could talk to the Pythia directly. She, a virgin priestess, sat on a tripod and in a trance, then shouted an answer back at you. It was the job of the priest to interpret her answer and feed it back to you as a hexameter verse, the typical meter of epic poetry. Then, with your cryptic poem received, you left.

This all sounds quite odd to us as modern readers, and it is our initial instinct to want to understand it a bit better from a scientific, psychological, anthropological or religious perspective (or some amalgamation of the lot). So, how exactly did the priestess receive her prophecies? The Greeks believed it was the god himself speaking through her, though some later sources like Plutarch doubt to what extent it was a god. However, all seem to be in agreement that she was in a trance of some kind, and that her words required interpretation - thus they could not be delivered directly to the client. So, let us examine some hypotheses as to what exactly may have driven her seemingly divine profession.

Undoubtedly, the most common opinion is that the priestess was intoxicated by fumes from the earth. This was the dominant theory proposed in the nineteenth century, when scholars decided to take a rational approach to deciphering ancient religion. This aligns neatly with the origin myth of the oracle, with her initially being influenced by Gaia, the goddess that personified the earth itself. Plutarch, our ancient oracle-skeptic, seems to argue a similar hypothesis, which ties into some of the greater themes of hellenistic philosophy involving humours and vapours, which is all a bit lost on me. As recently as 2003, there have been articles in academic journals attempting to prove this, the most recent being de Boer et al. who claimed to have traced two volcanic fault lines in the site and recorded evidence of ethylene and carbon dioxide emissions. Intoxication by either, so they argue, could have caused a trance akin to that described in our ancient sources.

This theory is immensely popular and the work of de Boer et al. was reported on widely, as it caused a minor sensation. There was no doubt mass appeal in their hypothesis and discoveries. However, the science has been much in debate before and after they published their article. Prior to their discoveries, the theory had been written off entirely due to two key factors: the lack of geographic evidence and the lack of medical evidence. Within a few years, the excitement driven by the publishing by de Boer and the team had driven more research. Not only did later research prove that their fault lines were mistakenly located, and could not have been in the sanctuary of the oracle, but doctors had claimed that a concentration of ~70% of this volcanic gas would have been required to cause this intoxication, an absolute improbability given the disproving of a fault line, but not entirely impossible. Further, the initial discovery was relying a bit too heavily on the works of Plutarch, who in the same treatise argued that garlic can stop magnets from working via the same principles that gave the oracle her visions. Perhaps not the best basis on which to ground your geological theories.

Another potential hypothesis is a form of manual intoxication, or, to put it in better English, drugs. Some ancient sources claim that the leaf of the Apolline bay could cause the trance. Evidence of opiate usage in the ancient world is often argued for. However, I have been unable to find any compelling evidence to support this theory, and one amusing anecdote in the service of disproving it. Allegedly, Prof. T. K. Oesterreich, an interesting looking fellow from the turn of the 20th century, consumed large amounts of this leaf and claimed he ‘did not feel any more inspired’. We cannot simply take an anecdote of a man, who appears to be a rather odd fellow from the minimal details I can find on him, as definite evidence to the contrary, but given the almost complete lack of evidence to support this theory, it is perhaps best to leave this one to rest.

A final possible explanation is a bit more boring than the others. This could simply be that the Delphians were quite aware of what they were doing, and that the oracle was either working herself up to appear in a trance or into some kind of odd psychological state. There is decent evidence to claim this frankly boring theory. The Delphians obviously profited massively from the continued function of the Pythia, as foreign dignitaries and important state officials flocked to seek advice, bringing in gold and influence in the cartload. Further, the oracle’s answers seemed to be suspiciously always on the side of whomever seemed the most beneficial to back at the time, which could later be written off as pure ambiguity or misinterpretation if needed. This intentional obscurity is noted even by contemporary sources like Heraclitus, who argues it to be a sign of the division between the mortal and immortal comprehensions of the world. The oracle dwelt in a grey area, in which her answers were neither true or false. However, she always seemed to stick particularly well to religious and political expectations, so perhaps either her or her interpreters had a hand in swaying the words to be a bit closer to what a customer wanted to hear.

To speculate about the oracle is all well and good, but it seems we may never know the truth of her trances. Perhaps that is for the best, as to attempt to analyse her from a purely scientific or psychological perspective is to somewhat miss the point. In a way, the prophecies she gave didn’t exactly matter. What the oracle stood for was more important. A religious institution, but also as a link between the known and the unknown. To travel to her and seek an answer then interpret the advice likely served to help people make their own decisions, then have an explanation if everything went wrong or perfectly. The purpose of the oracle was not to give a right answer, and we will probably never know how she operated. It would ruin the mystery. But also, more crucially, I suppose how she did it was never really the point. She acted as a compeller for human agency, imposing divine sanction onto whatever way you chose to act. Thus, she was an agent of human choice, at least that’s how I see her.

Sources

Homeric Hymns, tr. M. Rudden

Herodotus, Histories, tr. A. de Selincourt

Plutarch, On Oracles, extracts via H. Lloyd-Jones

de Boer, J.Z. et al. “Questioning the Delphic Oracle.” Scientific American 289, no. 2 (2003): 66–73.

Lehoux, D. “Drugs and the Delphic Oracle.” The Classical World 101, no. 1 (2007): 41–56.

Lloyd-Jones, H. “The Delphic Oracle.” Greece & Rome 23, no. 1 (1976): 60–73.

Kindt, J. “Delphic Oracle Stories and the Beginning of Historiography: Herodotus’ Croesus Logos.” Classical Philology 101, no. 1 (2006): 34–51.

Loved this. It's also key to remember thinking that the oracle was "real" or "fake" is looking at it through modern eyes. The ancient Greeks wouldn't have looked at it this way