Welcome to this week’s Dropout Classicist Article! Some of you may be aware I missed a week, but I am returning to form with the story of a poem that has long intrigued me, ever since I found the lines scribbled in the back of one of my notebooks. I hope you enjoy!

Today, I bring you a tale of discovery. One that stems from the oddest of places. We begin with a single line of Greek, turning into a long research tangent, culminating in a discovery off a charming poem and a potential redemption for one of mythology’s worst villains.

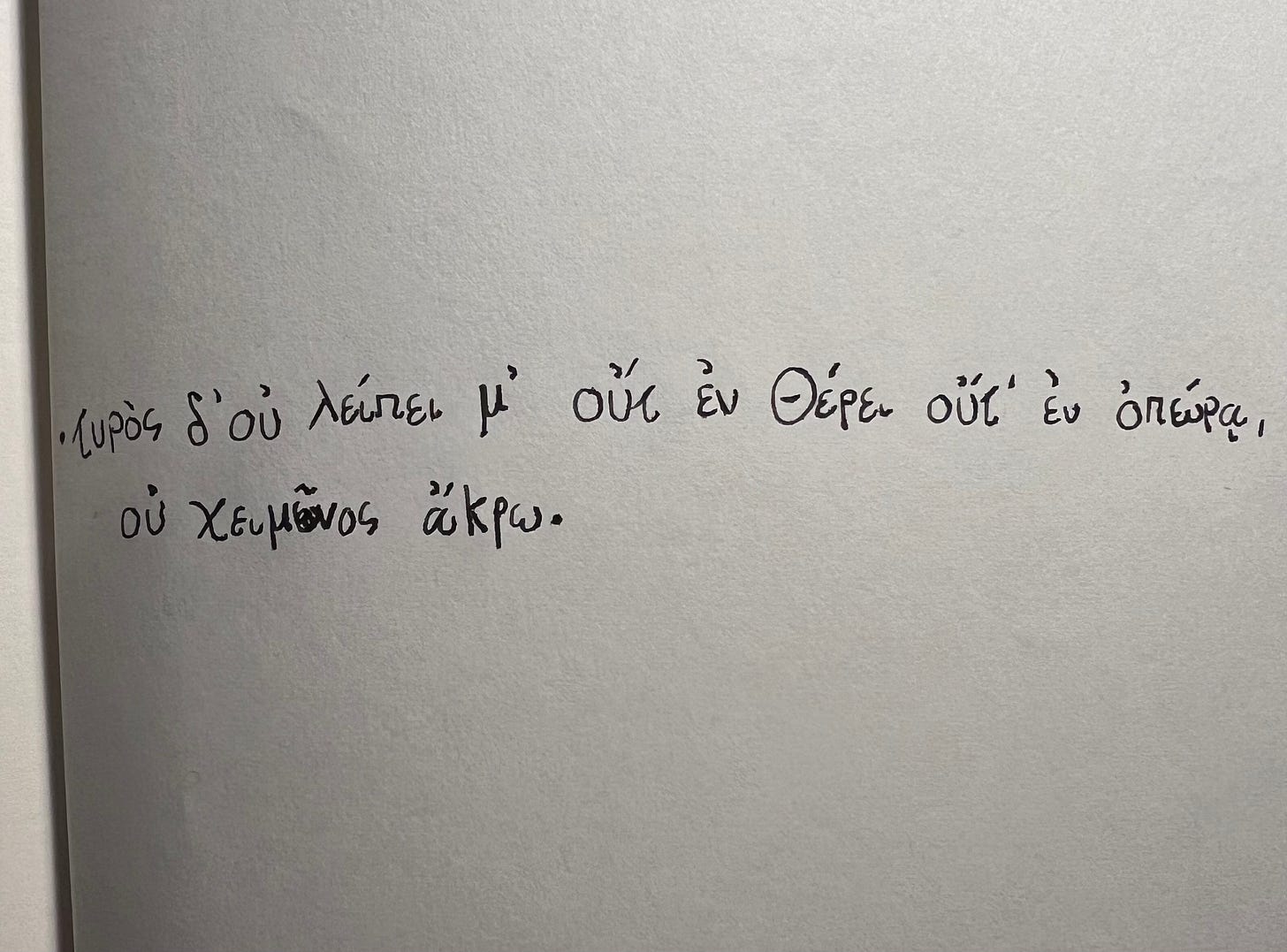

τυρος δ᾿ οὐ λειπει μ᾿ οὐτ ἐν θερει οὐτ ἐν ὀπωρᾳ, οὐ χειμονος ἀκρω·

"But cheese does not abandon me, neither in summer nor in autumn, nor at the end of winter"

This is a simple and sweet line of Greek poetry, which I found endlessly amusing, and I have no idea where I first found it. However, tracing back through my notes in my study of Ancient Greek, I see it recurring again and again. I must have found it amusing, and still do. It is oddly simple yet completely charming, and I do eat a lot of cheese. However, for almost as long as I have been scribbling this line on post-its and notebooks, I have wanted to know where it came from. Thus began my search.

Unfortunately, as it turns out, you can’t just google a random quote of Ancient Greek and expect it to turn up an author or work, at least not with the obscure or odd quotes like this. Thus, my search immediately became much more difficult than it needed to be. So, I put it off to the back of my mind and turned to more relevant things, confident I would return to it sooner or later. I did not have the time or effort to return to it for a while. Though, when I did, I was disappointed I hadn’t much sooner. I was missing out on an incredibly interesting poem.

So, my mysterious line of Greek ended up being a quote from Theocritus’ Idyll 11. Theocritus is not a well known author, and the title of his poem does little to sell it. However, I promise it is more interesting than it sounds. Theocritus was a poet from Sicily, the Italian island that became a Greek colony in the 8th Century BCE. Theocritus himself lived around 300 BCE, which was an odd time for the Mediterranean world. This was a period of transition, as the big powers of the 400s gave way to Macedonian conquest, and the centres of knowledge were moving away from Athens. Theocritus, though a little too early to fall among the Hellenistic poets, paved the way for pastoral poetry, which he is credited with inventing. This is a less dramatic form of poetry than the epic prioritised before it, focusing on country vistas and light-hearted love stories. It became a great favourite of the Romans, influencing Virgil and Horace.

You may not be particularly interested in poems about farming, and admittedly nor am I. If that were all this quote amounted to, I would have given up. However, I promised you cyclopes, and this is where they enter into the story.

Theocritus’ poetry still has a heavy focus on mythology, though admittedly in a less bloody way than most of the poets before him. Idyll 11, the poem in question, focuses on Polyphemus. Greek mythology nerds, or anyone who has read the Odyssey, may be a little confused by this. Polyphemus, in Homer’s poem, was a one-eyed, giant, man-eating, sheep-herding monster. How can such a figure be central to a whimsical poem? Well, I shall tell you.

The main narrative of the poem is far from anything we could picture Homer’s Polyphemus in. He finds himself the centre of a borderline Rom-Com, as the main plot of the poem is his lament over his love. Theocritus’ Polyphemus is thus immediately in stark contrast to the one we know from Homer, and this is used to great dramatic effect. The mythical monster is repurposed as a sort of rural idiot mixed with a bumbling and infantile yet sweet and besotted monster, tropes that appear often in both poetry and film, almost a King Kong or a Lenny from of Mice and Men. He is hopelessly devoted to the nymph Galatea (not to be confused with Galatea, who Pygmalion carves from marble and Aphrodite brings to life, the name of this bizarre Pinocchio is a mere coincidence). This Galatea has little agency in the poem, and disappointingly little to do or say, though she does reject Polyphemus, reasonably so.

A sympathetic portrayal of this figure is not quite what we would expect, given how horrendous he is in Homer. Theocritus’ version resembles this very little, yet he makes sure to remind us subtly that this is the same character. The first meeting of the two is an intentional parody of Odysseus meeting Princess Nausicaa in Book 6 of the Odyssey, yet with the roles reversed. In this, the cleaned Odysseus, (with, as Homer tells us, hair blossoming like a hyacinth) is ogled by the princess, though he is cautious and weary of her given his prior encounters with Calypso and Circe. Theocritus shows Polyphemus in the position of Nausicaa, in love innocently with Galatea, who is picking hyacinths. The repeated hyacinth motif is what ties this together for scholars, as Homer only mentions the flower twice in the Odyssey, this being the stand-out. The duality continues in strides. Nausicaa’s people, so Homer tells us, moved to Phaeacia to flee the cyclopes. Thus, Theocritus mirroring Homer’s scene is deeply ironic.

All this is well and good, but is the quote that actually started this quest at all relevant to the poem and its themes? Unfortunately, I could not find any scholarship on it. Thankfully though, I have my own opinions. Theocritus no doubt intends to make us pity Polyphemus. He is unlucky in love, begging to his mother that she may put in a good word to Galatea for him (this is another conscious mirror of the Odyssey, where Polyphemus begs his father Poseidon to punish Odysseus for blinding him). He shows us this unlucky and childish creature, unfortunate in his romantic errands, but also gives him an out. Though the narrative of the poem leaves Polyphemus loveless, he is consoled by his song and returns to his simple life. This is Theocritus’ moral for the poem, a theme he is very fond of. He is insistent that the best cure (pharmakon in Greek) for love is poetry. Thus, he takes the lovesick Polyphemus, cures him, and allows him to continue on with his satisfying simple life, at least for now. This is the relevance of my quote. His cheese, unlike his unrequited love, shall never abandon him. Perhaps this is a lesson we can all learn. Maybe Theocritus also feels a kinship for the Cyclops too. After all, he refers to him as a ‘fellow country-man’, as the Cyclopes were rumoured to have lived in his native Sicily, as we see in the likes of Virgil.

But wait, things get worse for our poor cyclops. Just as we were beginning to pity him, all of Theocritus’ constant references to the Odyssey come together in our mind. Polyphemus is consoled by his cheese and his sheep, yet we as readers know what is in his future. It is not long before a cunning Greek captain will enter his cave, blind him, steal his sheep, and, most crucially, rob him of his cheese! Alas, poor Polyphemus. He is not cured of his love-sickness for long. Theocritus manages to accidentally turn his relatively comedic love story into an unspoken tragedy. I must not be the only one for whom this has struck a chord, as the characterisation of the bumbling, lovesick Cyclops occurs later in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Ok, I will admit, I may be exaggerating a little. After all, Polyphemus is not pleasant in the Odyssey, and we do not pity him there. There is certainly an argument to be made that Odysseus is not in the right when he enters Polyphemus’ cave, helps himself to cheese and selfishly awaits gifts (see this post for more on the scene in Homer), a small and greedy crime against Greek Xenia (guest friendship). However, Polyphemus does brutally murder several of Odysseus’ men, so we can only feel so much pity when he has his eye poked out by Odysseus. Nonetheless, the stealing of the cheese is an indisputable tragedy, and I cannot help but feel a small twinge of pity for the idiotic cyclops, after Theocritus has humanised him.

In spite of this, the story does not have a great end. We may manage to spare a little sympathy for Homer’s portrayal of the Cyclops, despite his horrendous murder. However, in some versions of the myth, he does not take action that aligns with the sweet and simple image we are given by Theocritus. When we may depart Theocritus’ Polyphemus, he is content after singing out his woes. Theocritus even tells us he has more contentedness than gold, leaving him cured. However, he may not have taken this to heart. Some narratives have him killing Galatea’s lover with a rock. Not all interpretations can end happily I suppose!

Sources

Idyll XI - Theocritus

Metamorphoses - Ovid

The Odyssey - Homer

Whitaker, Richard. “AIMÉ CÉSAIRE AND THE CYCLOPS OF THEOCRITUS, ‘IDYLL’ 11.” Acta Classica 57 (2014): 246–48.

Liapis, Vayos. “POLYPHEMUS’ THROBBING ΠΟΔΕΣ: THEOCRITUS IDYLL 11.70–71.” Phoenix 63, no. 1/2 (2009): 156–61.

Holtsmark, Erling B. “Poetry as Self-Enlightenment: Theocritus 11.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 97 (1966): 253–59.

Prauscello, Lucia. “A Homeric Echo in Theocritus’ Idyll 11. 25-7: The Cyclops, Nausicaa and the Hyacinths.” The Classical Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2007): 90–96.

Alan H. F. Griffin. “Unrequited Love: Polyphemus and Galatea in Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses.’” Greece & Rome 30, no. 2 (1983): 190–97.

Newton, Rick M. “Poor Polyphemus: Emotional Ambivalence in ‘Odyssey’ 9 and 17.” The Classical World 76, no. 3 (1983): 137–42.

Glenn, Justin. “The Polyphemus Myth: Its Origin and Interpretation.” Greece & Rome 25, no. 2 (1978): 141–55.

Great take, especially the point about O abusing xenia, given what happens to the suitors. Does the line have any relationship to Fragment 94 of Alcman?

Thank you for your lovey poetic essay!